Information and Tips about Temples of Khajuraho

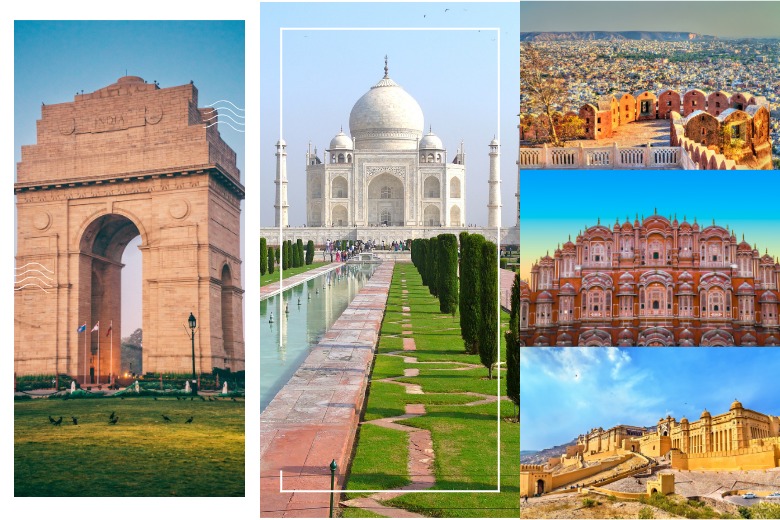

The Vidhya hills in Madhya Pradesh’s Chatarpur district form the back-drop to the small village of Khajuraho. Located 395 km (244 mi) southeast of Agra, this place is so rural that it’s hard to imagine Khajuraho as the religious capital of the Chandela dynasty (10th-12th centuries), one of the most powerful Rajput dynasties of Central India. The only significant river is some distance away, and the village seems far removed from any substantial economic activity. Yet this is where the Chandelas built 85 temples, 22 of which remain to give us a glimpse of a time when Hindu art and devotion reached their apex.

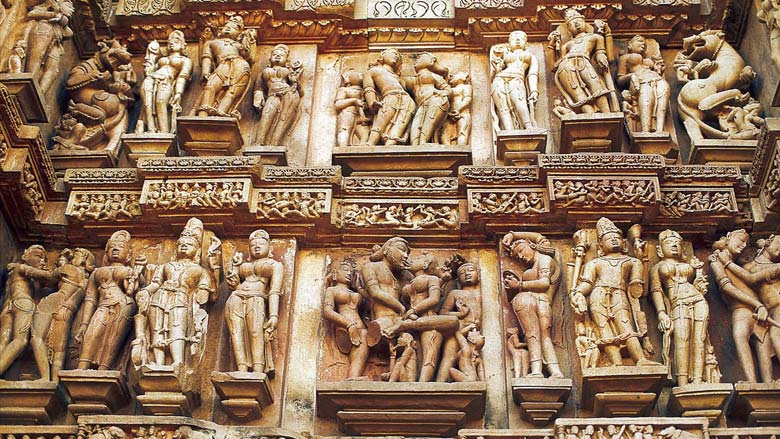

During the Chandelas’ rule, India was the Asian El Dorado. The temples’ royal patrons were rich, the land was fertile, and everyone lived the 10th-century good life, trooping off to fairs, feasts, hunts, dramas, music, and dances. This abundance was the perfect climate for creativity, and temple-building was emerging as the major form of expression. There were no strict boundaries between the sacred and profane, no dictates on acceptable deities: Shiva, Vishnu, Brahma, and the Jains’ saints were all lavishly honored, and new excavations have begun to uncover a complex of Buddhist temples as well. Despite the interest in heaven, the real focus was earth, and particularly the facts of human life. Here, immortalized in stone, virile men and voluptuous women cavort and copulate in the most intimate and erotic of postures. Temples of Khajuraho represents the best of Hindu temple sculpture: sinuous, twisting forms—human and divine—throbbing with life, tension, and conflict.

About khajuraho Temples

Book Madhya Pradesh tours with Swan Tours at best prices

The Chandela dynasty reigned for five centuries, succumbing eventually to invaders with a different moral outlook. In 1100, Mahmud the Turk began a holy war against the “idolaters” of India, and by 1200 the sultans of Delhi ruled over the once-glorious Chandela domain. Khajuraho’s temples lapsed into obscurity until their rediscovery by a British explorer in 1838.

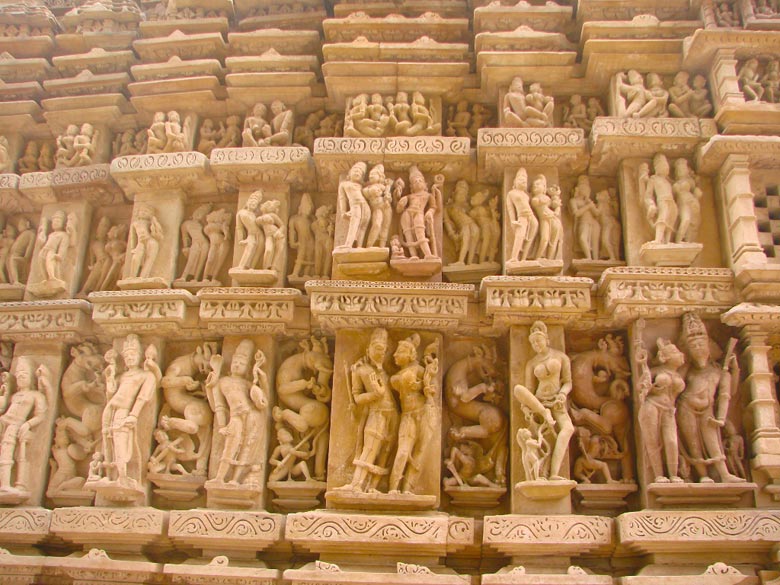

The temples have more to offer than erotic sculpture. Their soaring shikharas are meant to resemble the peaks of the Himalayas, abode of Lord Shiva: Starting with the smallest shikhara, over the entrance, each spire rises higher than the one before it, as in a range of mountains that seems to draw near the heavens. Designed to inspire the viewer toward the highest human potential, these were also the builders’ at-tempts to reach upward, out of the material world, to moksha—the final release from the cycle of rebirth. One scholar has suggested that Khajuraho’s temples were in effect chariots of the kings, carrying them off to a heavenly world resembling an idealized view of courtly life. Their combination of lofty structure and delicate sculpture gives them a unique sense of completeness and exuberance.

Of the 22 extant Temples of Khajuraho, all but two were made from sandstone mined from the banks of the River Ken, 30 km (19 mi) away. The stone blocks were carved separately, and then assembled as interlocking pieces to form a temple. Though each structure is different, every temple ob-serves precise architectural principle of shape form, and orientation and contains certain essential elements: a high raised platform, an ardh mandapam (entrance porch), a mandapam (portico), an antrala (vestibule), and a garbha griha (inner sanctum). Some of the larger temples also have a walkway around the inner sanctum, a mahamandapam (hall), and subsidiary shrines on each corner of the platform, making a complete panchayatana (five-shrine complex).

Khajuraho Temples

A number of sculptural motifs run through the temples. The directional gods, for instance, have designated positions on each temple. Elephant-headed Ganesh faces north; Yama, the god of death, and his mount, the male buffalo, face south. The two goddesses guarding the entrance to the sanctum are the rivers Ganges and Yamuna. Other sculptures include the apsaras (heavenly maidens), found mainly inside the temples, and the Atlas-like kichakas, who support the temple ceilings on their shoulders. Many sculptures simply reflect everyday activities, such as a dance class. The sultry nayikas (human women) show various emotions, and the mithunas are amorous couples. The scorpion appears as an intriguing theme, running up and down the thighs of many female sculptures as a kind of erotic thermometer. It appears, too, on the breastbone of the terrible, emaciated goddess Chamundi on the corners of several temple platforms, suggesting a complex and imaginative view of sexuality on the part of the sculptors and their patrons.

No one knows for sure why erotic sculptures are female important here, though many explanations have been offered. The female form is often used as an auspicious marker on Hindu gateways and doors, in the form of temple sculptures as well as domestic wall paintings. In the late classical and early medieval period, this symbol expanded into full-blown erotic art in many places, including the roughly contemporary sun temple at Modhera, in Gujarat, and the slightly later sun temple at Konark, in Orissa. Khajuraho legend has it that the founder of the Chandela dynasty, Chandravarman, was born of an illicit union between his mother and the moon god, which resulted in her ostracism. When he grew up to become a mighty king, his mother begged him to show the world the beauty and divinity of lovemaking.

Khajuraho Temples

A common folk explanation is that the erotic sculptures protect the temples from lightning; and art historians have recently noticed that many of the erotic panels are placed at junctures where some protection or strengthen-ing agent might be structurally necessary. Others say the sculptures reflect the influence of a tantric cult that believed in reversals of ordinary morality as a religious practice. Still others argue that sex has been used as a metaphor: The carnal and bestial sex generally shown near the bases of the temples represent uncontrolled human appetites, while the couples deeply engrossed in each another, oblivious to all else, represent a divine bliss, the closest humans can approach to God. Some also contend that the erotic is confined to the outer, worldly walls of the temples while their interior decoration is uplifting and focused on God, but this view is contradicted by the sculptures at several temples. The mystery lives on, but it’s clear that the sculptors drew on a sophisticated and sensual worldly heritage, including the Kama Sutra, the classical Hindu love manual, some of whose specific instructions are illustrated here.

The best way to see Khajuraho is to hire a guide (especially for the Western Group of temples) and to visit the Western Group in the first rays of the morning sun, follow them with the Eastern Group, see the museum in the afternoon, and make it to the Chaturbhuj Temple in the Southern Group in time for sunset.

Khajuraho holds an annual dance festival set in part against the back-drop of the temples. If you’ll be in India anytime around the beginning of March, don’t miss this superb event.

Eastern Group – Temples of Khajuraho

Interspersed around the edges of Khajuraho village, the Eastern Group of temples includes four Hindu and four Jain temples, whose proximity attests to the religious tolerance of the times in general and the Chandela rulers in particular.

Here is list of top Top 19 Temples of Khajuraho:-

#1. Vamana Temple

Vamana Temple of khajuraho

Northernmost is the late-11th-century Vamana Temple, dedicated to Vishnu’s dwarf incarnation (though the image in the sanctum looks more like a tall, sly child). The sanctum walls show unusual theological openness, featuring most of the major gods and goddesses; Vishnu appears in many of his form, including the Buddha, his ninth incarnation. Outside, two tiers of sculpture are concerned mainly with the nymphs of paradise, who strike charming poses under O their private awnings.

#2. Javari Temple

Javari Temple of Khajuraho

The small, well-proportioned Javari Temple, just south of the Vamana Temple and roughly contemporary in origin, has a simplified three-shrine design. The two main exterior bands bear hosts of heavenly maidens.

#3. Brahma Temple

Brahma Temple of Khajuraho

The granite and sandstone Brahma Temple, one of the earliest temples here (c. 900), is probably misnamed. Brahma, a titular member of the triad of Hinduism’s great gods, along with Shiva and Vishnu, rarely gets a temple to himself, and this one has a linga, the abstract, phallus-shape icon of Shiva. It differs in design from most of the other temples, particularly in the combination of materials and the shape of its shikhara.

#4. Ghantai Temple

Ghantai Temple of Khajuraho

South of these three temples, toward the Jain complex, is a little gem called the Ghantai Temple? All that’s left of this temple are its pillars, festooned with carvings of pearls and bells. Adorning the entrance are an eight-armed Jain goddess riding the mythical bird Garuda and a relief illustrating the 16 dreams of the mother of Mahavira, the greatest religious figure in Jainism and a counterpart to the Buddha.

#5. Adinath Temple

Adinath Temple of Khajuraho

The late-11th-century Adinath Temple, a minor shrine, is set in a small walled compound southeast of Ghantai. Its porch and the statue of Tirthankara (literally, “Ford-Maker,” a figure who leads others to liberation) Adinatha are modern additions. Built at the beginning of the Chandelas’ decline, this temple is relatively small, but the shikhara and base are richly carved.

#6. Parsvanath Temple

Parsvanath Temple of Khajuraho

The Parsvanath Temple to the south, built in the mid-10th century, is the largest and finest in the Eastern Group’s Jain complex and holds some of the best sculpture in Khajuraho, including images of Vishnu. In contrast to the intricate calculations behind the layout of the Western Group, the plan for this temple is a simple rectangle, with a separate spire in the rear. Statues of flying angels and sloe-eyed beauties occupied with children, cosmetics, and flowers adorn the outer walls. The stone conveys even the texture of the women’s thin garments.

#7. Shantinath

Shantinath

The third temple in this cluster, the Shantinath, bears an inscription dating it to the early 11th century. it has been remodeled extensively and is still in active use, but it does contain some old Jain sculpture.

Southern Group – Temples of Khajuraho

#8. Duladeo Temple

Duladeo Temple of Khajuraho

Though built in the customary five-shrine style, the Duladeo Temple (about 900 yards south of the Eastern Group’s Ghantai) looks flatter and more massive than most Khajuraho shrines. Probably the last temple built in Khajuraho, dated to the 12th century; the Duladeo Ternple lacks the usual ambulatory passage and crowning lotus-shape finials. It has some vibrant sculptures, but many are clichéd and over decorated. Here, too, in this temple dedicated to Shiva, eroticism works its way in, though the amorous figures are discreetly placed.

#9. Chaturbhui Temple

Chaturbhui Temple of Khajuraho

The small, 12th-century Chaturbhui Temple, nearly 3 km (2 mi) south of Duladeo, has an attractive colonnaded entrance and a feeling or verticality thanks to its single spire. It enshrines an impressive four-handed image of Vishnu that may be the single most striking piece of sculpture in Khajuraho. With a few exceptions, the temple’s exterior sculpture falls short of the local mark (a sign of the declining fortunes of the empire), but this temple is definitely the best place in Khajuraho to watch the sun set. A few hundred yards north of the Chaturbhuj Temple are excavations for the newly discovered Buddhist complex, which archaeologists first announced in 1999. It will be years before reconstructions are complete, but you may find a recently unearthed piece of sculpture on view.

Western Group – Temples of Khajuraho

Most of the Western Group is inside a formal enclosure with an en-trance off Main Road, opposite the State Bank of India. The grounds are open daily from sunrise to sunset, and the admission fee, Rs. 1, includes the museum.

#10. Chausath Yogini Temple

Chausath Yogini Temple of Khajuraho

The first three temples, though considered part of the Western Group, 0 are actually at a slight distance from the enclosure. The Chausath Yogini Temple, on the west side of the Shivsagar Tank, a small artificial lake, is the oldest temple at Khajuraho, possibly built as early as AD 820. It is dedicated to Kali, and its name refers to the 64 (Chausath) female ascetics (yoginis) who serve this fierce goddess in the Hindu pantheon. Unlike its counterparts of pale, warm-hued sandstone, this temple is made of granite and is the only one (so far excavated) in Khajuraho that’s oriented northeast-southwest instead of north-south. It was originally surrounded by 64 roofed cells for the figures of Kali’s attendants; only 35 cells remain. Scholarly supposition holds that this and a handful of other open-air temples, usually circular, in remote parts of India were focal points for an esoteric cult.

#11. Lalguan Mahadeva

Lalguan Mahadeva Temple of Khajuraho

The Shiva temple Lalguan Mahadeva is a few hundred yards north-east of the Chausath Yogini. The structure is in ruins, and the original portico is missing, but this temple is historically significant because it was built of both granite and sandstone, marking the transition from Chausath Yogini to the later temples.

#12. Matangesvara Temple

Matangesvara Temple of Khajuraho

Just outside the boundary of the Western Group is the Matangesvara Temple, the only one still in use here; worship takes place in the morning and afternoon. The lack of ornamentation, square construction, and simpler floor plan date this temple to the early 10th century. The building has oriel windows, a projecting portico, and a ceiling of overlapping concentric circles. An enormous linga, nearly 81/2 ft tall, is enshrined in the sanctum.

Across the street from Matangesvara, Khajuraho’s Archaeological Museum has some exquisite carvings and sculptures recovered by archaeologists. The three galleries attempt to put the various sculptures into context according to the deities they represent.

#13. Varaha Temple

Varaha Temple of Khajuraho

As you enter the Western Group complex, you’ll see the Varaha Temple (circa 900-925) to your left. This shrine is dedicated to Vishnu’s Varaha avatar, or. Boar Incarnation, which Vishnu assumed in order to rescue the earth after a demon had hidden it in the slush at the bot-tom of the sea. In the inner sanctum, all of creation is depicted on the massive and beautifully polished sides of a stone boar, who in turn stands on the serpent Shesha. The ceiling is carved with a lotus relief.

#14. Lakshmana Temple

Lakshmana Temple of Khajuraho

Behind the Varaha Temple stands the Lakshmana Temple, also dedicated to Vishnu, and the only complete temple remaining. Along with Kandariya Mahadeva and Vishvanath (LG. below), this edifice represents the peak of achievement in North Indian temple architecture. All three temples were built in the early to mid-10th century, face east, and follow an elaborate plan resembling a double cross, with three tiers of exterior sculpture above the friezes on their high platforms. The ceiling of the mandapam is charmingly carved with shell and floral motifs. The lintel over the entrance to the main shrine shows Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and consort of Vishnu, with Brahma, Lord of Creation (on her left) and Shiva, Lord of Destruction (on her right). A frieze above the lintel depicts the planets. The relief on the doorway shows the gods and demons churning the ocean to obtain a pitcher of miraculous nectar from the bottom. The wall of the sanctum is carved with scenes from the legend of Krishna (one of Vishnu’s incarnations). An icon in the sanctum with two pairs of arms and three heads represents Vishnu as Vaikuntha, or the supreme god, and is surrounded by images of his ten incarnations. Around the exterior base are some of Kimpjuraho’s most famous sculptures, with gods and goddesses on the protruding corners, erotic couples or groups in the recesses, and apsaras and sura-sundaris (apsaras performing everyday activities) in-between. Along the sides of the tall platform beneath the temple, friezes depict social life, including battle scenes, festivals, and amorous sport.

#15. Kandariya Mahadev

Kandariya Mahadev Temple of Khajuraho

The Kandariya Mahadev, west of the Lakshmana Temple, is the largest and most evolved temple in Khajuraho in terms of the blending of architecture and sculpture, and one of the finest in India. Probably built around 1020, it follows the five-shrine design; and its central shikhara, which towers 102 ft above the platform, is actually made up of 84 subsidiary towers building up in increments. The feeling of ascent is repeated inside, where each succeeding mandapam is a step above the previous one, and the garbha griha is higher still; dedicated to Shiva, this inner sanctum houses a marble linga with a 4-ft circumference. Even the figures on this temple are taller and slimmer than that elsewhere. The rich interior carving includes two beautiful toranas (arched doorways); outside, three bands of sculpture around the sanctum and transept bring to life a whole galaxy of Hindu gods and goddesses, mithunas, celestial handmaidens, and lions. A total of 872 statues-226 in-side and 646 outside—have been counted.

#16. Devi Jagdamba Temple

Devi Jagdamba Temple of Khajuraho

The Devi Jagdamba Temple was originally dedicated to Vishnu, as indicated by a prominent sculpture over the sanctum’s doorway. It’s now dedicated to Parvati, Shiva’s consort, but because her image is black—a color associated with Kali, goddess of wrath and an avatar of Parvati—it is also known as the Kali Temple. From the inside, its three-shrine design makes the temple appear to be shaped like a cross. The third band of sculpture has a series of erotic mithunas. The ceilings are similar to those in the Kandariya Mahadev, and the three-headed, eight-armed statue of Shiva is one of the best cult images in Khajuraho.

#17. Mahadeva Temple

Mahadeva Temple of Khajuraho

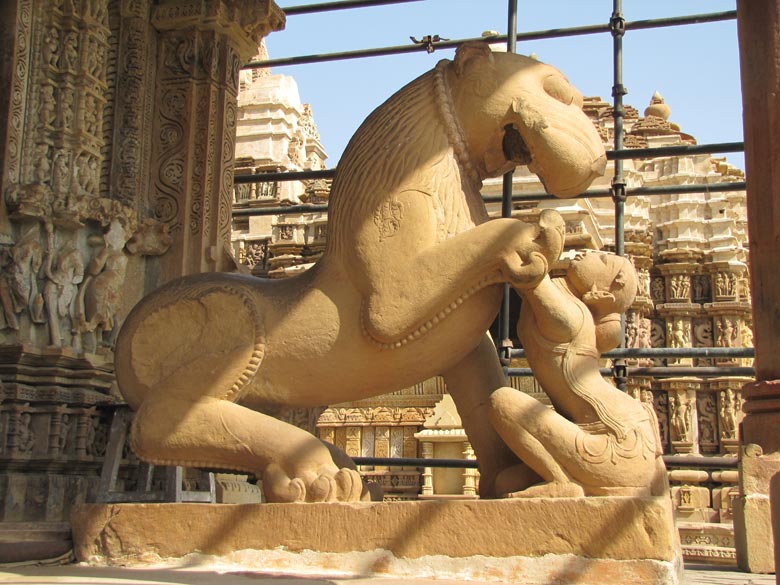

The small, mostly ruined Mahadeva Temple shares its platform with the Kandariya and the Devi Jagdamba. Now dedicated to Shiva, it may originally have been a subsidiary to the Kandariya Mahadev temple, probably dedicated to Shiva’s consort. In the portico stands a remarkable statue of a man caressing a mythical horned lion.

#18. Chitragupta Temple

Chitragupta Temple of Khajuraho

The Chitragupta Temple lies slightly north of the Devi Jagdamba and resembles it in construction. In honor of the presiding deity, Surya—the sun god,the temple faces east, and its cell contains a 5-ft image of Surya complete with the chariot and seven horses that carry him across the sky. Surya also appears above the doorway. In the central niche south of the sanctum is an image of Vishnu with 11 heads; his own face is in the center, and the other heads represent his 10 (9 past and 1 future) incarnations. A profusion of sculptural scenes of animal combat, royal processions, masons at work, and joyous dances depict the lavish country life of the Chandelas.

#19. Vishvanath Temple

Vishvanath Temple of Khajuraho

The Vishvanath Temple is on a terrace to the east of the Chitragupta and Devi Jagdamba temples. Two staircases lead up to it, the northern flanked by a pair of lions and the southern by a pair of elephants. The Vishvanath probably preceded the Kandariya, but here two of the original corner shrines remain. On the outer wall of the corridor surrounding the cells is an impressive image of Brahma, the three-headed Lord of Creation, and his consort, Saraswati. On every wall the form of woman dominates, portrayed in all her daily 10th-century occupations: writing a letter, holding her baby, studying her reflection in a mirror, applying makeup, or playing music. The nymphs of paradise are voluptuous and provocative, and the erotic scenes, robust. An inscription states that the temple was built by Chandela King Dhanga e in 1002. Facing the main temple, a simpler shrine, the Nandi Temple, houses a monolithic statue of Shiva’s mount, the massive and richly harnessed sacred bull Nandi. ED The small and heavily rebuilt Parvati Temple, near Vishvanath, was originally dedicated to Vishnu. The present icon is that of the goddess Ganga standing on her mount, the crocodile.

For more information on visit to the Temples of Khajuraho, contact Swan Tours – One of the leading travel agents in India promoting tourism since 1995.