About Ajanta Caves

It is thought that a band of wandering Buddhist monks first came here in the 2nd century BC searching for a place to meditate during the monsoons. Ajanta was ideal—peaceful and remote, with a spectacular set-ting: a sharp, wide horseshoe-shape gorge that fell steeply to a wild mountain stream flowing through the jungle below. The monks began carving crude caves into the rock face of the gorge, and a new temple form was born.

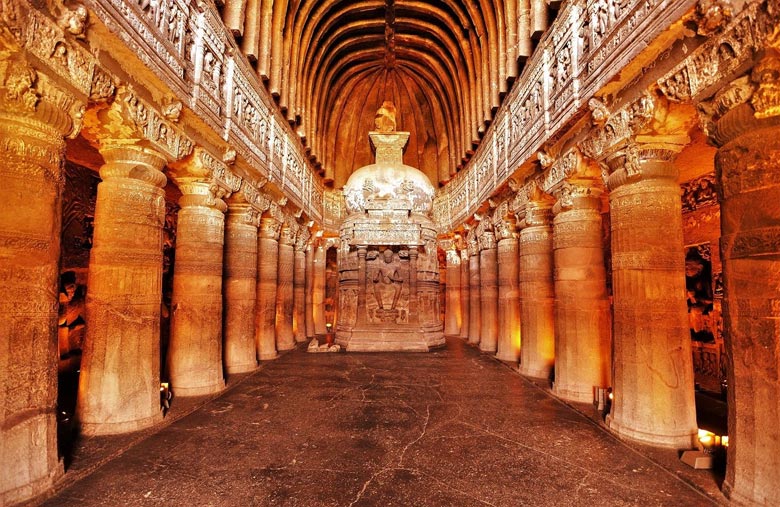

Over seven centuries, the cave temples of Ajanta evolved into works of incredible art. Structural engineers continue to be awestruck by the sheer brilliance of the ancient builders, who seem to have created this marvel of artistic and architectural splendor undaunted by the limitations of their implements, materials, and skills. In all, 29 caves were carved, 15 of which were left unfinished; some of them were viharas (monasteries)—complete with stone pillows carved onto the monks’ stone beds—others were chaityas (Buddhist cathedrals). All of the caves were profusely decorated with intricate sculptures and murals depicting the many incarnations of Buddha.

Buddhist Cathedrals

As Buddhism declined, the monk-artists abandoned their work, and the temples were swallowed up by the jungle. A thousand years later, in 1819, Englishman John Smith was tiger-hunting on a bluff nearby in the dry season and noticed the soaring arch of what is now dubbed Cave 10 peeking out from the thinned greenery; it was he who subsequently unveiled the caves to the modern world.

At both Ajanta and Ellora, monumental facades and statues were chipped out of solid, particularly hard rock, but at Ajanta, an added dimension has survived the centuries—India’s most remarkable cave paintings. Monks spread a carefully prepared plaster of clay, cow dung, chopped rice husks, and lime onto the rough rock walls and devotedly painted pictures on it with only natural local pigments: red ocher, burnt brick, copper oxide, lampblack, and dust from crushed green rocks. The caves are now like chapters of a splendid epic in visual form, re-calling the life of the Buddha and illustrating tales from Buddhist jatakas (fables). As the artists lovingly told the story of the Buddha, they portrayed the life and civilization they knew; the effect is that of a magic carpet flying you back into a drama of ancient nobles, wise men, and commoners. When the electric spotlights flicker onto the paintings, the figures seem to come alive.

Opinions vary on which of the Ajanta caves are most exquisite. Caves 1, 2, 16, 17, and 19 are generally considered to have the best paintings, Caves 1, 4, 17, 19, and 26 the best sculptures. (The caves are numbered from west to east, not in chronological order.) The guides hanging around the entrance to the caves are useless at best: Don’t waste your money. The attendants at each cave, however, can be helpful.

Most popular at Ajanta are the paintings in Cave 1, depicting the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara and Bodhisattva Padmapani. Padmapani, or the “one with the lotus in his hand,” is considered the alter ego of the Lord Buddha, who assumed the duties of the Buddha when he disappeared. Padmapani is depicted with his sinuous-hipped wife, one of. Ajanta’s most widely reproduced figures.

Ellora Caves

Cave 2 is remarkable for its ceiling decorations and its murals relating the birth of the Buddha. For its sheer exuberance and joie de vivre, the painting of women on a swing is considered the finest.

Sculpture is the main interest in Cave 4. The largest vihara in Ajanta, this one depicts a man and a woman fleeing from a mad elephant and a man giving up his resistance to a tempting woman.

The oldest cave is Cave 10, a chaitya dating from 200 BC, filled with Buddhas and dominated by an enormous stupa. It is only in AD 100, however, that the exquisite brush-and-line work begins. In breathtaking detail, the Shadanta Jataka, a legend about the Buddha, is depicted on the wall in a continuous panel.

The mystical heights attained by the monk-artists reach their zenith in Cave 16, where you’re released from the bonds of time and space. Here a continuous narrative spreads both horizontally and vertically, evolving into a panoramic whole—at once logical and stunning. One painting here is riveting: Known as “The Dying Princess,” it is believed to represent Sundari, the wife of the Buddha’s half-brother, Nanda, who left her to become a monk. Cave 16 has an excellent view of the river and may have been the entrance to the entire series of caves.

Ellora Caves

Cave 17 holds the greatest number of pictures undamaged by time. Luscious heavenly damsels fly effortlessly overhead, a prince makes love to a princess, and the Buddha tames a raging elephant. Other favorite paintings include the scene of a woman applying lipstick and one of a princess performing sringar (her toilet).

A number of unfinished caves were abandoned mysteriously, but even these are worth a visit if you can haul yourself up a steep 100 steps. You can also walk up the bridle path, a gentler ascent in the form of a crescent pathway alongside the caves; from here you have a magnificent view of the ravines of the Waghura River.

A trip to the Ajanta caves needs to be well planned. You can see the caves at a fairly leisurely pace in two hours, but the drive to and from the caves takes anywhere from two to three hours. Come prepared with water, snacks (from a shop in Aurangabad; there are no snack stands here), comfortable walking shoes, a flashlight, and patience. Aurangabad can be hot year-round, and peering into a succession of 29 caves can be tiring. The paintings are only dimly lit (to protect the art-work) and a number of them are badly damaged, so deciphering the work takes some effort. The caves are connected by a fair number of steps, both up and down; it’s advisable to start at the far end and work your way back, to avoid a hot trek back at the end. Flash photography and video cameras are both prohibited inside the caves; the ad-mission fee includes having the lights turned on as you enter one.

About Ellora Caves

In the 7th century, for some inexplicable reason, the focus of activity shifted from Ajanta to a site 123 km (76 mi) to the southwest—a place known today as Ellora. Unlike the cave temples at Ajanta, those of Ellora are not solely Buddhist. Instead, they trace the course of religious development in India—through the decline of Buddhism in the latter half of the 8th century, the Hindu renaissance that followed the return of the Gupta dynasty, and the Jain resurgence between the 9th and 11th centuries. Of the 34 caves, the 12 to the south are Buddhist, the 17 in the center are Hindu, and the five to the north are Jain.

At Ellora the focus is on sculpture, which covers the walls in exquisitely ornate masses. The carvings in the Buddhist caves are a serene reflection of the Buddhist philosophy, but in the Hindu caves they take on certain exuberance, a throbbing vitality. Gods and demons do fearful battle, Lord Shiva angrily flails his eight arms, elephant’s rampage, eagles swoop, and lovers intertwine.

Unlike Ajanta, where the temples were chopped out of a steep cliff, the caves at Ellora were dug into the slope of a hill along a north-south line, presumably so that they faced west and could thus receive the light of the setting sun.

Cave 1 (two stories) and Cave 3 (three stories) are remarkable for having more than one floor. The two caves form a monastery behind an open courtyard. The facade looms nearly 50 ft high, but it’s simple, belying the lavish interior beyond. Gouged into this block of rock are a ground-floor hall, a shrine above that, and another hall on the top story with a gallery of Buddhas seated under trees and parasols.

Ellora Caves

The largest of the Buddhist caves is Cave 5, 117 ft by 56 ft. This was probably as a classroom for young monks. The roof appears to be sup-ported by 24 pillars; working their way down, sculptors first “built” the roof before they “erected” the pillars.

Cave 6 contains a statue of Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of learning—also identified as Mahamayuri, the Buddhist goddess of learning—in the company of Buddhist figures. Cave 10 is the “Carpenter’s Cave,” where Hinduism and Buddhism meet again. Here the stonecutters re-produced the timbered roofs of their day over a richly decorated facade that imitates masonry work. Inside this chaitya—the only actual Buddhist chapel at Ellora—the main work of art is a huge image of Buddha.

The immediate successors to the Buddhist caves are the Hindu caves, and a step inside these is enough to pull you up short. It’s another world—another universe—in which the calm contemplation of the seated Buddhas gives way to the dynamic cosmology of Hinduism. Thought to have been created around the 7th and 8th centuries, these kinetic sculptures depict goddesses at battle; Shiva waving his eight arms; life-size elephants groaning under their burdens; lovers striking poses; and boars, eagles, peacocks, and monkeys prancing around what has suddenly turned into a zoo.

Ellora is dominated by the mammoth Kailasa temple complex, or Cave 16. Dedicated to Shiva, the complex is a replica of his legendary abode at Mount Kailasa in the Tibetan Himalayas. The largest monolithic structure in the world, the Kailasa reveals the genius, daring, and raw skill of its artisans.

To create the Kailasa complex, an army of stone cutters started at the top of the cliff, where they removed 3 million cubic ft of rock to create a vast pit with a freestanding rock left in the center. Out of this single slab, 276 ft long and 154 ft wide, the workers created Shiva’s abode, which includes the main temple, a series of smaller shrines, and galleries built into a wall that encloses the entire complex. Nearly every surface is exquisitely sculpted with epic themes.

Around the courtyard, numerous friezes illustrate the legends of Shiva and stories from the great Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. One interesting panel on the eastern wall relates the origin of Shiva’s symbol, the linga, or phallus. Another frieze, on the outer wall of the main sanctuary on the southern side of the courtyard, shows the demon Ravana shaking Mount Kailasa, a story from the Ramayana. The Jain caves are at the far end. If you have a car, consider driving there once you’ve seen the Hindu group of caves. The Jain caves are attractive in their own right and should not be missed on account of geography. Cave 32, for one, is as complex as a rabbit burrow; it’s marvelous to climb through the numerous well-carved chambers and study the towering figures of Gomateshvara and Mahavir.

Ellora is said to be the busiest tourist site in the state of Maharashtra. The Ajanta caves are a bit off the beaten track, but Ellora, a mere half an hour from Aurangabad, bristles with crowds—honeymooners, picnic-wallahs, and students—and is none too peaceful. Try to avoid coming here during school holidays.

For Customized tours to Ajanta and Ellora caves contact Swan Tours, One of the leading Travel Agents in India.