Information on Art and Crafts of Rajasthan

Jaipur is a city built on a formalized, square grid but the bustle, colour and vibrant rhythm of its streets prevent one from perceiving it. Extensive areas of Rajasthan are monotone, beige-brown desert, but the dramatic spectacle and visual variety that pervade it make it one of the most vibrantly colourful of Indian states. These paradoxes are seen again and again — a recurring motif reflected in its decorative arts and crafts.

It is one of the poorest and and least industrially developed parts of India, yet it houses the most opulent and rich treasures. Its history is a long saga of blood feuds and violent battles, but the forbidding stone battlements of its forts shield mirrored rooms and marble carvings of delicacy and grace.

The same high-balconied prisons that prevented women from venturing out into the outside world were marvels of exquisite ornamentation. The jewelled belts and anklets that proclaimed their status as ornamental chattels were at the same time rich symbols of love and pride.

Here is list of Art and Crafts of Rajasthan:-

Mughal influence

Mughal influence in Rajasthan

Rajas who sacrificed wealth, power, territory, life itself, to withstand the Mughals, generation after generation, at the same time borrowed freely from Mughal art and aesthetics, taking styles, symbols and techniques, often stealing artisans, and incorporating them into their own eclectic, rich tradition.

Some contrasts, however extreme, seem almost inevitable. It seems natural that a landscape so parched and brown should produce paintings bursting with vibrant flowers and foliage and running water; that people starved of natural colour and beauty should almost obsessively decorate everything — be it a camel or a king’s crown; that warriors going into battle should arm themselves with delicately decorated, jewelled shields and swords.

Other contradictions are more inexplicable, even reprehensible. Why were women forced to spend their lives embroidering garments to embellish themselves, and sat, bejewelled and bedecked, locked away in mirrored rooms, merely so their husbands could view them and boast of their virtue and beauty?

Rajasthan and its crafts are a source of endless fascination — whether one approaches them for purely visual, aesthetic pleasure or pauses to savour the underlying history, culture and symbolism.

Behind the main squares and streets of its cities, Jaipur, Ajmer Udaipur, Jodhpur, and in every village, artisans still live, practicing crafts handed down orally generation to generation. It is worth bypassing the big tourist souvenir emporia and going to watch the craft-workers themselves in action.

Just as one’s eye, dazzled by the colour and pageantry of Jaipur streets, forgets the geometric symmetry of their right-angled layout, the richness and colour of Rajasthani craft can lead one to forget the religious or cultural symbolism from which they derive their inspiration, but colour, shape and motif also have meanings. To ignore them is to miss much.

The Indian stone-mason carves “frozen lace” filigree on the sandstone trellised balconies of Jaisalmer with four basic tools: a pointed punch or tanki, a cold chisel or pahuri, a hatora (hammer) and a barma (borer). But the principals underlying the carving were laid down in the Manasara and Shilpshastras, Sanskrit texts on art and aesthetics dating back 2000 years. For example, the height, width and diameter of every shaft, arch and building detail is strictly defined. Within these formal principles individual creativity can run riot. One generation finding inspiration in flowing arabesques of peacocks and poppy flowers another in Mughal-inspired geometric’ squares and stars.

Colour — a vital element of much Indian design — is supplied by the dyer and the printer. Each town and village has some distinctive skill. On both sides of the road from Jodhpur to Udaipur via Pali, lengths of material gleam in the sun as they dry on tall sticks, and the printing process continues by the river.

Expert dyers

Expert dyers

In Alwar a few families still exist who are able to perform the apparently miraculous feat of dyeing one side of a sari red and the reverse side of it green, without any overlapping of colour. In Kota they dye the warp one colour and the weft another to create a shot effect. All over Rajasthan the bandhani, tie-dyed sari, veil and turban can be found.

Different designs have different names. Laharia is the diagonal-striped version, done mostly in Udaipur; chira, when the stripes are of variegated colours; chunari is the dotted one; ekdali has small circles and squares; tikhunti, chaubandi and satbandi, have groups of three, four, and seven dots respectively; in dhannak the designs form flowering circles; in jaldar and beldar, the dots form diagonal or flowering patterns; shikari is a design with human, tiger, horse and elephant figures. Patterns may be simple or complex, the technique is the same: the cloth is bleached and washed repeatedly to remove all starch and chemicals, and the design block-printed on with washablegeru (earth colour). The village women then take over, their left hand thumb and little finger nail specially kept long for this purpose. They push and pinch the fabric up into small points which they tie with two or three twists of thread. When dyed, the knotted parts remain uncoloured. The more intricate bandhanis are tied and dyed several times: separately for each colour, starting with th( lightest one.

Weaving of all kinds is practiced as a cottage industry. Men and women, and sadly often their children as well, steal a few hours from the fields to sit down at the pit loom in their courtyard and weave a few inches of a durry (cotton carpet), a goat-hair blanket or intricately patterned camel-hair bag. Camels, peacocks, eight-pointed stars or the triangles of a tented settlement are familiar stylized motifs. The fine self-checked cotton saris of Kota are famous, and the people of p Jaipur make beautiful woollen knotted carpets in the Mughal tradition.

Block printing, too, is a traditional art of Rajasthan, and towns like Sanganer and Bagru have been devoted exclusively to this occupation since medieval times; their products exported as far afield as China, Europe and the Middle East. The towns of Sanganer, Barmer and Bagru between them produce about 250,000 metres (275,000 yards) of printed fabric a day, all printed by hand with carved wooden blocks also made locally. Sanganer specializes in delicate floral Patterns, Barmer in red and indigo geometric ajraks, Bagru in brick and black, linear and zigzag stripes. The motifs and layouts are delicate and subtle; the colours are spectacular. Fabrics with stunning combinations of scarlet and shocking pink, purple and orange, turquoise and parrot green, saffron and crimson, often shot with gold and silver, and set with shining mirrors, are worn by women as flared skirts, veils or saris, and sometimes by men as colourful turbans.

Until recently the dyes were vegetable and earth colours extracted from flowers, bark, roots and minerals: jasmine, saffron and myrobalan producing oranges and yellows; mulberry bark and the kirmiz insect, reds and purples; indigo and pistachio galls, blues and greens; sulfate of iron, black. The ingenuity of the Indian dyer knew no bounds, with over 250 different shades in common use in the mid-19th century, with a very successful green being extracted from the soaked green baize exported from England for billiard tables.

Woven, dyed and block-printed, the fabric is then further embellished by embroidery. Though Rajasthani women, curiously enough, seldom stitch their own clothes, depending on the local tailor to do this, they do embroider them. Skirts, bodices and veils, as well as coverlets and decorative pieces for their homes, are covered with beautiful, often ad-lib designs of dancing figures and flowers, peacocks, the tree of life and the mandala (a circular religious motif). The Barmer region is known for its flat, geometric, surface satin-stitch motifs, other areas use chain and herringbone stitch, and worn fabric is excitingly recycled into stunning patchwork quilts, cushions and shoulder bags.

Wealth of silver

Rajasthani

Clothes — their colour, design and cut — may tell people which village and caste someone comes from, but it is jewellery in which people’s wealth is invested. In the Rajasthani villages it is silver. Huge, heavy chunks of it are worn around ankles, waist, neck and wrists, dangling in rings from ears, nose and hair, in chains of buttons down kurta or choli fronts. The beautiful, ornate designs of Adivasi jewellery have now become fashionable among the urban Elite, and can he bought everywhere. Silver is too soft to be durable on its own and is generally mixed with copper before being worked. The silver in the shops ranges from 65 to 90 percent pure silver, and prices vary accordingly. Jewellers will assure you that their silver is 95 percent pure. Pure silver has a coarse, dull sound when struck, unlike the shrill, vibrating sound of other metals. Apart from jewellery, Rajasthan’ silversmiths make beautiful boxes, trays, small statues of Krishna and Ganesh, and ornamental objets d’art—birds, horses and elephants, enamelled as well as plain.

The aristocracy and the well-to-do did not wear silver. Kundan and enamel jewellery inlaid with precious stones was a speciality of Rajasthan, particularly of Jaipur. Rajasthan is rich in precious and semi-precious stones. Emerald, garnet, agate, amethyst, topaz and lapiz lazuli are all found locally. Other stones came from further afield as the fame of the Jaipur jewellers and gem-cutters spread. Men as well as women wore elaborate jewellery, and the hilts and scabbards of swords and daggers, goblets and condiment boxes were all equally heavily ornamented.

Unlike European jewellery, though stones were sometimes etched or embossed into decorative shapes and patterns, they were not cut or faceted to remove flaws or accentuate colour. The size of the stone and the elaboration of its setting rather than its depth of colour or brilliance were of greater importance. The back of each piece, set in heavy gold kundan or jarao, was embellished with delicate enamel ornamentation using the champleve (raised field) technique. The design, usually entwined flowers and birds, sometimes human and animal figures, was hollowed out, each colour segment separated by a fine raised gold line and the enamel painted in and fired. Each colour was fired separately, in a furnace sunk deep into the ground, starting with those requiring greatest heat. The enamel colours and techniques have poetic names: ab-e-leher, waves of water; tote-ka-par, parrot’s wing; and hkun-e-kabutar, pigeon’s blood (a most highly prized deep translucent red).

Each piece of jewellery is formed by a specialised chain of crafts: the nyarriya refines the gold, the sangsaz, polishes and cuts the stones; the manihar prepares the enamel; the sonar makes the bezels for setting the stones and fashions the jewel, using patterned moulds; the chattera engraves the ground; the minakar enamels and fires it; the kundansaz sets the stone in a mixture of lacquer and antimony and, when it has solidified, cold-sets it with hammered gold wire. The sonar polishes and cleans the piece and the patwari puts the finishing touch of twisted gold and silk cord, with its tasseled pendant and beaded knot, twisting the threads in an intricate cat’s-cradle between a big toe, knee and index finger.

Stones and metals are also symbolic of the deities of the Hindu pantheon, the nine planets of the Indian astrological system, and sacred sites or rivers. For example, diamond denotes both Agni and Venus, sapphire the god Vishnu as well as Saturn, ruby Indra and the sun, etc. Gold and silver symbolise the sacred rivers Ganga and Yamuna.

To complicate matters further, each gem is supposed to have both positive attributes and flaws. For example, the pearl protects the wearer from evil, and a house where pearls are kept “is chosen by the ever-fickle God-dess of Wealth, Lakshmi, as her permanent abode”, but a pearl of the wrong shape or colour can cause leprosy, loss of sons, poverty or death. Emeralds, which cleanse you of sin, according to Sanskrit texts, can bring wealth and success in war, and protection from poisoning, but here again, the wrong colour or shade or flaw can cause disease, fatal wounds in battle, or even, apparently, death by snakebite.

The skilled gem-cutters of Jaipur also carve enchanting little animals and birds from rock crystal, jade, smoky topaz and amethyst, and you can buy intaglio beads and buttons, and crystal scent bottles as well. The Wearing of highly coloured decoration iS not restricted to women, Rajasthani men traditionally won, vibrant and embellished clothes, form the stiff starched furl of a saffron or shocking-pink. turban (8 metres/9 yards of it twirled into convoluted folds weighing, more than 2 kilos/4 pounds) to the tips of the turned-up toes of the traditional juthis.

The juthis or slippers are made of locally tanned and flayed leather. Each village has its own community of a few families who practice this trade, collecting dead animals from the local farmers and making juthis for them. For centuries they were considered outcastes, but this did not mean they were not consummate craft-workers. The leather was tanned and dyed by vegetable and mineral formulae handed down from generation to generation, and made into shoes and sandals, water bags, fans, pouches and saddles, and musical instruments. It was embroidered, punched, gouged, studded, sequined and stitched in a variety of intricate designs, varying from region to region sequins and tassels in one village, brass studs and machine-stitched motifs in another. Men did the tanning, cutting and stitching, women the embroidery and ornamentation. Most of the slippers and sandals are available in the big cities – Jaipur, Jodhpur and Ajmer. They are incredibly sturdy, being made to withstand waterlogged fields, wind and weather, and they pinch and squeak excruciatingly for the first few days. Persevere and they become the most yielding, comfortable footwear you have ever worn, and certainly the longest lasting.

In Bikaner the inner hide of the camel is put to another use. It is scraped till it is translucent and tissue-fine and then molded into perfume bottles, water jugs, vases and lamp shades, painted with delicately gilded gesso-work floral designs.

Interior decor

Rajasthanis decorate themselves

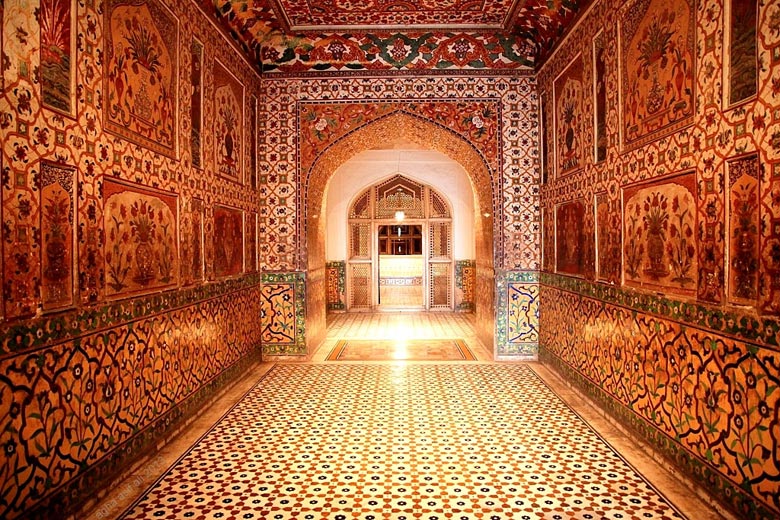

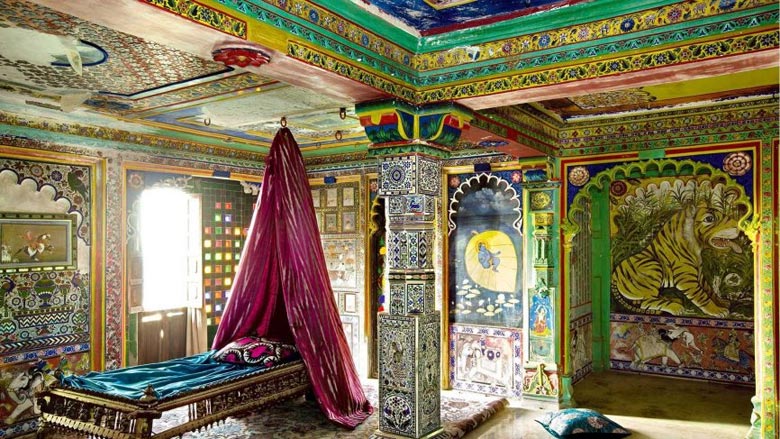

In the same way as Rajasthanis decorate themselves, they also decorate their homes. The walls of their dwellings, be they palaces or huts, are painted and decorated. The palaces with inlaid mirror mosaics or marble engraved in floral bas-reliefs set with precious stones; the village homes and city walls with murals of elephants and tigers, illustrations of legends of gods and goddesses, or scenes of everyday life. Doors, windows, pillars and balconies are carved and fretted, inlaid with brass, ivory or mother-of-pearl, or painted. Domestic furniture is also often carved and decorated — chests, chairs, cradles and low tables, inlaid with brass sheet-work or — in the past — ivory, or painted with dancing Radhas and Krishnas. Shekhavati and Jodhpur are famous centres for wood-carving. Jaipur specializes in brass-wire inlay on ebony and sheshum wood. Fine brass wires are set in intricately intertwined geometric or floral patterns and made into ornamental boxes, trays and mirror-frames. The minutely carved wooden blocks used for textile printing are so exquisite that nowadays they are bought by tourists for their own sake. Udaipur is noted for its mirror and mother-of-pearl inlay, Bikaner for its plaster and gold gesso murals, Jaipur for its marble carving, and Jaisalmer for the incredibly intricate stone jalis (lattices).

Most of the motifs found in the painted wood and wall murals derive from the miniature and pichwai paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries, when every small Rajput ruler had at least one painter in their entourage. They were commissioned to paint court portraits, scenes from the epics, incidents from history, and make records of local flora and fauna which were then incorporated by court artisans into their textiles, carpets and carvings. Each court had a distinctive style of painting — the attenuated, elegant figures of Kishangarh with their soaring eyebrows and sidelong smile; the elaborately detailed court and battle scenes of Mewar; the Bikaner horses and Kota hunting scenes; the harsh simplicity of Bundi.

Done on paper made from cotton, jute or bamboo fibre polished to smoothness with an agate stone, the artist first did a line sketch ingeru terracotta, covering it with a coat of white. This was then painted on with mineral and vegetable colours ground and extracted from indigo, lapiz, cochineal, cinnebar, mercury sulphite and orpiment, as well as pure gold dust, using squirrel-hair brushes often as fine as one hair. The paintings had no perspective, but intricate details of clothes, jewellery and head-dresses were meticulously rendered, and natural scenes were vividly portrayed, uninhibited by considerations of seasons or climatic conditions. Both in the paintings made for the royal courts and the pichwai cloth hangings used in the temples, the Radha-Krishna legend was a favourite theme, depicted in a Ragamala series, each painting linked to a musical mode in turn associated with seasons, months, days and hours and personifications of different phases of love and emotion, both temporal and spiritual.

Phad paintings, with their brilliant flaming orange, red and black stylized cartoon strip illustrated scrolls, are a more popular art form. They are used by the Bhopas, itinerant epic singers who play at fairs and festivals to the accompaniment of the jantar, a bamboo stick zither with two gourd resonators. Their songs, and the phads, recount the legend of Papuji Ramdeo of the Rabari tribe and his famous black mare, whose neigh warned him of danger; or of Dev Narainji, another Robin Hood-type hero.

Miniatures, pichwais and phads are all still being painted today, but are fast becoming slick, assembly-line copies. Simultaneously, copies of Audubon birds, Redoute roses’ Japanese geisha prints and Persian’ manuscripts are all being turned out to meet the demand of the market. The skills are still there, although the patrons and inspiration have changed.

Miniature paintings were also done on ivory in Udaipur and Nathdwara. The smooth, matte surface was a perfect foil for the delicate, stylized pictures highlighted with gold.

Ivory is traditionally a popular medium in Rajasthan, from the heavy bracelets worn by Bhil women, to delicate carvings and inlay work. Ivory dust is used medicinally in both the unani and ayurvedic schools of Indian medicine for abdominal disorders. Ivory is subject to a world-wide ban on exports — do not attempt to take it out of the country — and bone is often used in its place.

Muslim artisans specialize in metal-work. The of all kinds, especially brass enamel are two types, Sadha and siya kalann. In sadha, the brass is coated with a thin layer of tin which is then cut to reveal the pattern in the underlying brass. gleaming in constrast to the tin. Insiva kalam, the design is left in relief. and the rest of the surface cut away. The depressions are tilled with black lac or coloured enamel — red. White, pink or green. When finished, the relief pattern in plain brass stands out against the coloured enamel. There are three different styles — chikan, marori and bidri, each with its repertoire of traditional motifs and designs.

Another metal inlay technique is damascening done by the swordsmiths and armourers of Udaipur and Alwar, whose wonderful shields, swords and armour were chased with floral arabesques, hunting scenes or calligraphic Koranic verses, depending on the tastes of Rajput or Mughal patrons. They now make cutlery, areca-nut crackers, butttons and paper knives to suit the needs of a less belligerent age. Pratapgarh gold filigree and enamel is another beautiful, unusual, but dying craft. Court, religious or hunting scenes are cut out of a fine gold sheet and the resulting silhouette relief mounted onto a backing of deep red or blue enamel and set in box tops or as decorative plaques.

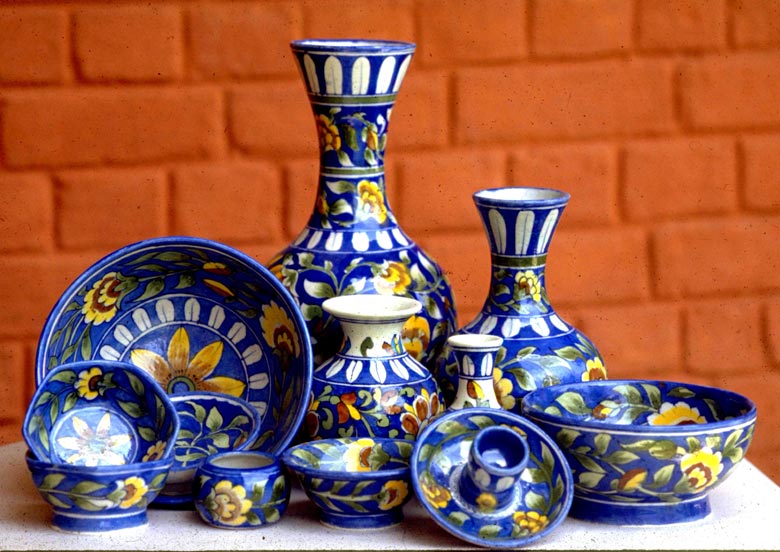

Distinctive to Jaipur today, through originally Iranian and Turkish in origin, is the famous Blue Pottery. It is unique in that no clay is used. It is made from a mixture of fuller’s earth, quartz and sodium sulphite that needs firing only once. It is made in moulds with only the neck and lip turned on the wheel. Its characteristic turquoise blue is made from copper sulphate extracted from old scrap metal and the deep blue is cobalt oxide. Most of the pottery made today is formulaic, but a visit to the studio of Kripal Singh Shekhavat, a local painter, shows a different side of the craft. Borrowing inspiration from Persian miniatures and the Ajanta, frescoes, and reintroducing long-forgotten colours such as pinks, greens and yellows into the glaze, he has taken traditional shapes and forms and revitalised them.

All over Rajasthan, village potters turn less elaborate but equally beautiful jars, water-pots, urns, and utensils for the local market. Made of unglazed red terracotta, their simple, perfectly proportioned shapes are a blend of utility and elegance that industrial designers often strive for. Their creation is deceptively simple, but it requires great skill. They appear from a lump of mud on a roughly shaped wheel, all it seems to take is a spin and a flick of dextrous thumb and forefinger, and the pot is ready.

Come festival time. The potter will turn to creating tiny toys and images — elephants and chariots, many-armed Devi. Mounted warriors, caparisoned camels, and tiny lamps. These beautiful lamps, normally lit by oil wicks, are traditionally made for the festival of Divali,when they are used to light up Rama’s path back to Ayodhya from his battle against Ravanna in Lanka.

The pressures on Rajasthani artisans, as on all Indian traditional skills, are great. More and more of their products are deteriorating into mass-produced knick-knacks for the unwary tourist. Exploitive middlemen urge craft workers to produce in the quickest possible time at the lowest possible price. What then emerges can be a rather unworthy object with just a faint flicker of its former glorious self. The tourist can help by being selective about what they buy. Some shops, such as the chain Anokhi, pay a fair price for their products and support schemes that empower women and do not use child workers. Children are often exploited as a source of cheap labour, and travellers should not buy goods produced in this way —shopping in government stores and buying directly from the producers are two ways to ensure that either the money goes straight to the workers, or that they have at least a degree of protection.

The strength of Rajasthani crafts is that they have always been embedded deeply in the everyday lives of the people and were not merely produced for the court or urban market. They are part of the social structure and an abiding cultural tradition. It is this that has helped Rajasthani crafts to survive the stresses of technology, the tourist trade and ever-changing life-styles. They have suffered and changed, but are still recognisably the product of a vibrant society.

Swan Tours can customise Art and Crafts Tours of Rajasthan , which depend on the number of days that you wish to spend in Rajasthan , The destinations which can be visited during the Art and Crafts Tours of Rajasthan can be Mandawa , Bikaner , Jaisalmer , Jodhpur , Udaipur , Jaipur and many more . For more information contact Rajasthan Travel expert at Swan Tours – One of the leading Travel agents in India, Some of the sample itineraries of Rajasthan are as below: